Bills establishing credit programs for low carbon fuels, including those derived from landfills and other waste sources, are proliferating in state houses around the country.

A clean fuel, low carbon fuel, or clean transportation standard sets a timeline for fuel producers to gradually reduce the emissions, or carbon intensity, of their product, either by blending in existing low-carbon fuels like ethanol or buying credits from producers of fuels that emit even less carbon, like renewable natural gas derived from landfill gas or anaerobic digestion.

Their spread has been fueled by some unlikely coalition partners, and may be gaining steam thanks to the success of California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard and other early models that first appeared on the West Coast, proponents say. If more states create such programs, they’re likely to boost the so-called “brown rush” that’s already capturing the attention of some of the waste industry’s largest players and netting them millions of dollars in new revenue.

“You really can't get to a zero emission future if you don't have an LCFS, because if you don't have carbon neutral fuels, it's impossible,” Todd Campbell, vice president of public policy and regulatory affairs at RNG producer Clean Energy Fuels, said. “This is really helping us move in that direction, and I think that the opportunities are just starting to show to many folks, especially if you're in the waste industry.”

A ‘win-win’ situation

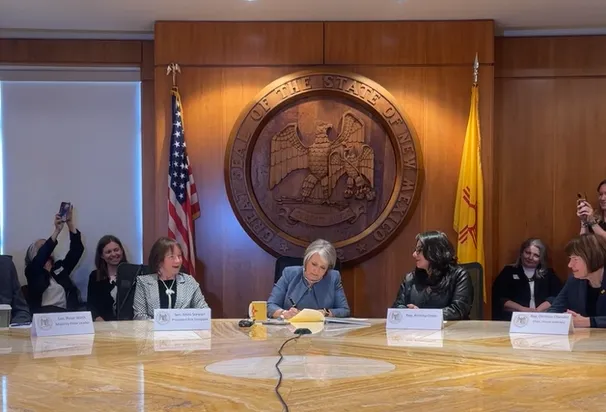

In early March, New Mexico became the fourth U.S. state to enact a clean fuel standard program after Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed House Bill 41. The bill sets a goal to reduce the carbon intensity of transportation fuels used in the state by 20%, and includes provisions to ensure that rural electric cooperatives common in the state can participate, along with traditional biogas producers.

"This is one of those win-win, win-win, no one loses, pieces of legislation," Grisham said at a press conference announcing the bill's signature.

New Mexico is one of the country's largest producers of fossil fuel oil and natural gas, and has a comparatively small biofuels industry. The state currently has just 16 facilities producing biogas: 12 of those are wastewater treatment plants, three are landfills and one is a manure-based digester, according to data from the American Biogas Council.

But with supportive policies like a clean fuels program, the industry group projects the state could host as many as 144 such facilities, taking into account existing landfills, farms and an estimate of currently wasted food that could be beneficially reused. Those facilities could produce up to 13.7 million mmBtus per year, the equivalent of heating 892,000 homes in New Mexico.

That potential has long held the attention of the state's Democratic governor and her allies, who have been pushing to pass a clean fuels bill for about four years. Proponents say they’ve watched renewable diesel and other fuels produced in Texas get shipped through New Mexico and into California, and say they can now court those producers themselves.

“Let's rethink how these fuels are being produced, transported and used and make sure that those renewable diesel trucks, they stop here,’” Michelle Miano, director of New Mexico’s Environmental Protection Division, said.

Across the country, states are taking notice of the economic impact of California’s program. There are eight states with active bills in their legislatures today, and groups ranging from the Midwest to the East Coast are increasingly eager to see programs enacted.

For several years, the U.S. EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard has driven a large portion of revenue for biogas projects. Clean Energy Fuels, a biogas developer with six active facilities and several more in development, still derives far more revenue from federal RIN credits created by the RFS than from California’s program, according to its financial report for 2023.

But if more states continue to pass legislation of their own, they could dramatically expand the revenue opportunities for fuels generated from waste, especially in heavily populated areas like New York and New Jersey. As these ideas enter the mainstream, though, they’ll face scrutiny from environmentalists eager to move toward electrification and a hungry oil and gas sector looking to maximize its stake in a burgeoning alternative fuels sector.

The country’s largest waste companies have pivoted to RNG in recent years to take advantage of incentives created by the LCFS and its companion programs.

Republic Services, which declined to comment for this story, plans to direct 50% more biogas from its facilities to beneficial reuse by 2030. Meanwhile, WM recorded $273 million in net operating revenues from its renewable energy business last year, which includes RNG, and names “federal and state incentive programs” as a primary driver of growth for the business segment in its end of year filings for 2023.

WM is also supportive of new state clean fuel programs in states like New Mexico, New York and Minnesota, “the three states with the most momentum for potential legislative enactment,” John Skoutelas, vice president of legal and national director of government affairs, said in an emailed statement.

Big oil’s about-face

The seed of California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard was first planted by the state’s Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, signed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. It came at a time when the U.S. was just beginning to blend ethanol into petroleum, nearly a decade before the Paris Agreement formalized a global response to the climate crisis.

First approved by the California Air Resources Board in 2009 and implemented in 2011, the LCFS spurred a flurry of litigation from the oil and gas industry. That staunch opposition continued when Oregon decided to follow California’s lead and implement its own clean fuels program in 2012.

“The oil industry was not necessarily too excited about another regulation that required them to reduce greenhouse gases,” Tim Zenk, managing director at climate strategy firm Earth Finance, said. “They fought it tooth and nail.”

But those challenges largely proved fruitless, and the programs themselves began to pay off. In the decade since it was implemented by the California Air Resources Board, the LCFS has reduced greenhouse gas emissions from transportation by 137 million megatons of carbon dioxide equivalent and spurred $4 billion of investment in renewable fuels infrastructure, according to an agency spokesperson.

Today, California has certified the carbon intensity of 441 facilities producing methane fuel from biogenic sources. Of those facilities, 188 are dairy manure digesters and 192 are landfills, according to data from the agency.

The oil and gas industry began to take notice of the program’s success. In 2020, BP left a regional oil and gas lobbying group in part over its opposition to Washington state's clean fuel standard proposal. The company instead elected to take a neutral stance on the bill, the Seattle Times reported at the time.

Since then, BP has ramped up its pursuit of biofuels while supporting clean fuel programs legislation in several states, though not in New Mexico, where it has limited operations. BP's blockbuster acquisition of landfill gas firm Archaea Energy in 2022 for more than $4 billion accelerated those efforts. BP now has a goal to increase its biogas supply volumes sixfold by 2030.

ExxonMobil has also made major investments in renewable diesel, including Canada’s largest renewable diesel project. Facilities like that one, along with projects from Valero, Chevron, Marathon and others, have flooded California’s LCFS credit market, which now faces a credit surplus as capacity continues to come online.

“The obligated parties, the Shells, the BPs, the Totals, the Chevrons, they started out having to buy credits … Then they took a further look into this and said, 'What's a better compliance strategy?' Well, it's to get on board,” Campbell said. “Now they're not just buyers of these credits, they're active market participants, and they're converting their refineries to renewable diesel refineries instead of crude oil refineries.”

That about-face has cleared the way for clean fuel programs in new states, including New Mexico. There, ExxonMobil and Oxy both came out in support of the proposal, which would support further renewable diesel production in the state and allow the companies to burnish their image on climate, Robin Vercruse, executive director of the Low Carbon Fuels Coalition, said.

“New Mexico itself is opening a lot of eyes. People are saying, ‘Wow, New Mexico can do this, they’re the number two oil and gas state in the country. Why can’t we do this?’” Vercruse said.

The rush to invest in alternative combustible fuels rather than electrification spurred by these clean fuels programs is giving environmental groups pause. Kiki Velez, equitable gas transition advocate for the Natural Resources Defense Council, argues that the LCFS is in need of reform after more than a decade of supporting such fuels.

In the NRDC’s view, clean transportation programs today should be focused on incentivizing electric transportation and reserving biofuels for truly hard-to-decarbonize sectors, as policies like the Advanced Clean Fleets rule already do. They point to research showing that the LCFS has channeled more than $5.8 billion to farm-based digester projects and crop biofuels, and argue future investment would be better spent elsewhere.

“When [the LCFS] was initially developed, it was a race to see what's going to be the correct fuel and/or other energy resource that's going to be used to decarbonize the transportation sector,” Velez said. “There wasn't a clear winner yet at that point. Now we know, and CARB has already stated, that all-electric is the path forward.”

Copying California’s homework

The federal government has threatened the fuels industry with legislation and regulation in the past, but the push and pull of competing oil and gas versus agriculture interests have made the prospect of a national clean fuels program infeasible. That might not be such a bad thing, Zenk said.

Zenk, who spent several years working with alternative fuels producer Sapphire Energy as the West Coast clean fuels programs came online, said each new program brings the opportunity for localization.

In Washington, the state included environmental justice-related provisions that require air pollution mitigation near disadvantaged communities and ensure other program benefits, like charging infrastructure, are specifically sited in those communities. Zenk said states that are debating clean fuel programs today can address the particularities of their greenhouse gas challenges by working at the state level — the share of Hawai’i’s transportation greenhouse gas emissions coming from aviation is double that of Washington, for instance.

As new programs come online, they can now refer back to the structure of California's LCFS and the carbon intensities for different fuels set by the California Air Resources Board as part of the program, saving administrative costs as a result, Dana Adams, state legislative policy manager for the Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas, said.

"CARB can say, 'Your process from x digester, y treatment, to here, to your end use, has a carbon intensity negative 10,' for example. Then Oregon can look at that and say, 'Okay, CARB already did the math. Let's just copy their homework,'" Adams said.

Each state can also choose how aggressive it wants to be in its carbon reduction pathway. Oregon, for instance, is currently ratcheting up carbon intensity reduction targets at a faster clip than California’s current pathway, though CARB is exploring a tighter pathway of its own.

Perhaps the most enticing state for renewable fuel producers is New York, where the League of Conservation Voters’ local chapter has spent the past three years building support. A clean fuel standard bill that would have set a 20% reduction target by 2031 passed the state Senate but failed to gain traction in the Assembly. This year, advocates are hoping to pass it either as part of the state budget or as a standalone bill, Patrick McClellan, director of policy at the New York League of Conservation Voters, said.

The group has also found some unlikely allies. It leads a coalition that includes major airlines, ethanol producers, automakers and biogas groups. BP is also lobbying for a program in New York, but McClellan said the coalition has set a hard rule preventing oil and gas companies from joining.

While it may seem awkward to see a conservation group and fossil fuel supermajor aligned, McClellan said the New York League of Conservation Voters came by the issue organically, and said it was no different than supporting offshore wind projects at a time when oil producers are bidding on the projects.

“If they want to be supporting it, that’s great, the more the merrier,” McClellan said. “We do see this as a really important piece of the puzzle for decarbonizing transportation.”

New York’s biogas potential is huge — the American Biogas Council estimates that the state has the potential to build more than 300 new facilities, most of which would be in the manure space. At full buildout, the state could produce 52.3 million mmBtus of heat per year, nearly four times as much as New Mexico.

Beyond the raw numbers on gas potential, enactment in New York and New Jersey would be an influential shift that would allow clean fuel programs to gain a foothold on the East Coast, Campbell, with Clean Energy Fuels, said. He noted that while it takes time for proposals to gestate in state legislatures, once they catch on, they can make an impact.

“I will be very excited to see both New York and New Jersey adopt this kind of standard,” Campbell said. “Those states, when they adopt a Clean Fuel Standard, it won't be as big as California, but it certainly shows that these are important policies for other states to consider.”