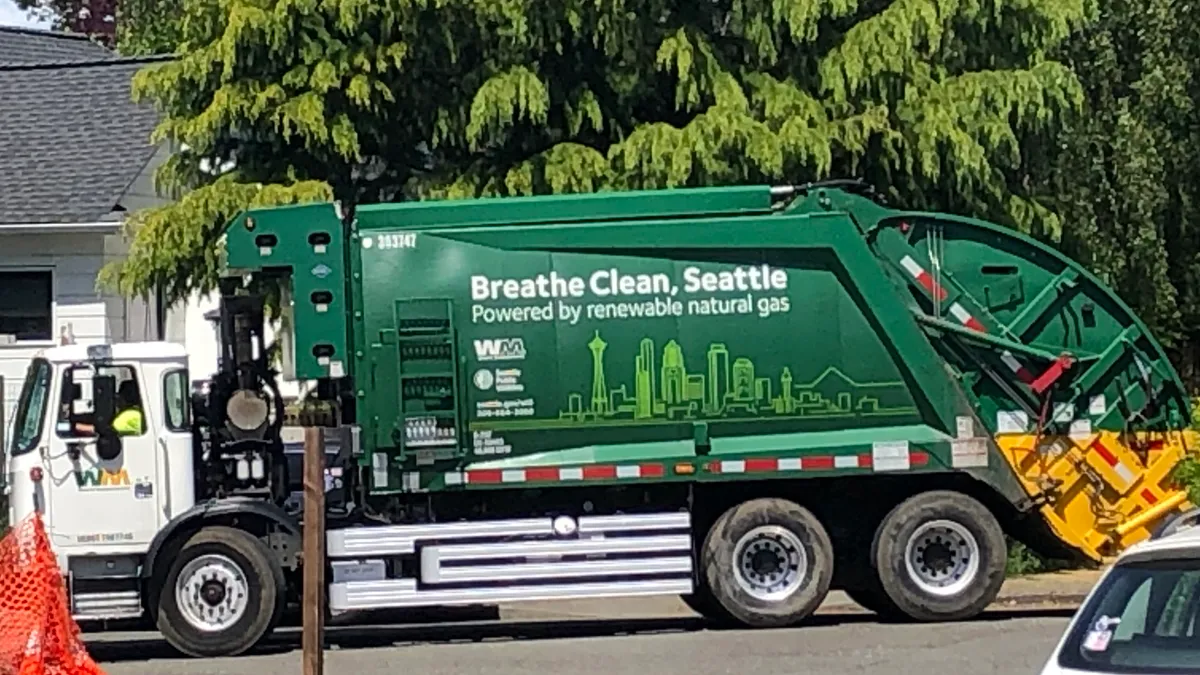

WM is in discussions to alter the branding on its Seattle trucks that advertise they're "Powered by renewable natural gas" after pressure from environmental activists who say the ads are greenwashing.

A public pressure campaign, led by environmental group GasLeaks, began in February to urge more transparency in WM’s RNG commitments. It has since drawn the attention of officials, including the Seattle City Council and Seattle Public Utilities, who now say they’re working to make changes.

“Capturing methane is a good thing; methane is a climate super pollutant and we really need to get control of it if we really want to avoid the worst climate outcomes,” Caleb Heeringa, campaign director with GasLeaks, said. “But it becomes a problem when it is used to make the public believe that the gas system itself is a permanent part of a climate-safe future.”

SPU confirmed that WM is complying with its contract, which requires 100% RNG from landfill credit. It also said it’s working with WM to remove the slogans from the hauler’s trucks, saying in an emailed statement that they’re “vague and could lead to confusion.”

WM’s current commercial waste contract with Seattle was finalized in 2018, at the same time as a related contract with Recology, and began in April 2019. The contract required WM to use CNG-fueled vehicles from model year 2018 or newer to meet the RNG-sourcing requirement, and also mandated that both haulers pilot the use of electric vehicles.

WM defended its RNG practices in an emailed statement, noting it’s producing and claiming RNG credits through the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard program.

“The starting point for this conversation is that WM is acting in compliance with our contract with the City of Seattle,” WM spokesperson Jackie Lang said. “We are achieving this compliance through the allocation of RNG to the trucks servicing the city consistent with standard industry practice.”

The controversy over how WM is fueling its trucks laid bare the mixed public perception of waste-derived natural gas as a clean fuel. It has also frustrated members of the biogas industry who argue the Seattle issue is a misunderstanding of the RNG market.

Patrick Serfass, executive director of the American Biogas Council, said RNG works like any other renewable power source, and the complaints from environmental groups about WM using RNG credits for its Seattle fleet fail to give credit to the market used to support cleaner energy projects.

“It's not just standard for the way that you buy and sell and claim the use of renewable natural gas, it's what you do to buy and sell and claim the use of renewable anything,” Serfass said.

Municipal contracts nationwide have increasingly mandated that collection fleets run on alternative or lower emission fuels, including some electric vehicles, as a method of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The potential for refining and reusing landfill-sourced natural gas is significant for companies like WM. The company is planning a rapid expansion of RNG collection capabilities at its landfills, and it has the highest proportion of CNG vehicles in its fleet among publicly-traded major waste companies. But the sector is still limited compared to the nation’s overall natural gas demand.

In a 2013 study, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that landfills, wastewater and other waste sources could generate up to 7.9 million metric tons of methane per year, enough to displace about 5% of electric power sector natural gas consumption and 56% of transportation-related natural gas consumption. That’s led environmentalist groups like GasLeaks to be skeptical of efforts to ramp up RNG production, preferring to see landfill gas handled in other ways — like converting it to electricity on site.

GasLeaks’ February report noted that none of WM’s nearby landfills collected and refined biogas into RNG. The nearest non-WM landfill, the Cedar Hills Regional Landfill, does collect gas that it feeds into area pipelines, but it accounts for 0.3% of pipeline volume.

Heeringa, whose organization was joined by nonprofit 350 Seattle and Sierra Club’s Seattle Group in urging change, said his objection is that RNG has been used by the natural gas industry to argue that its systems can be cleaned up despite the lack of biogas capacity.

He considers Seattle Public Utilities’ decision to have WM take down the ads a “win,” but he’d still like to see proof that WM has enough RNG credits to negate the natural gas it’s using for its Seattle fleet.

“It's quite possible that they are complying here with that, but the ads themselves still lead the public to believe that it's literally, physically biogas in the trucks,” Heeringa said. “That contributes to public misconception about biogas' ability to be a climate solution going forward.”

WM said it is exploring adding RNG capability to its Columbia Ridge Landfill in Arlington, Oregon, which manages waste from Seattle. At an investor presentation on April 5, Shahid Malik, WM’s vice president of renewable energy, explained plans to build 20 new RNG facilities in three years that would add 25 million mmBtus of output. WM’s current RNG output is roughly 3 million mmBtus.

WM's fleet report to the City of Seattle, obtained by GasLeaks, indicated it used about 58,000 mmBtus for truck operations in 2020. In response to questions, Lang said the company has “allocated RNG available through the Renewable Fuel Standard for Seattle since October 2016.”

“This allocation has matched 100% of our fuel use for the city with brief and isolated exceptions, such as severe weather interruptions and meter downtime,” Lang said.